Eudaimonia

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| It has been suggested that Eudaimonism be merged into this article or section. (Discuss) |

- For the saturniine moth, see Eudaemonia (moth).

Eudaimonia (Greek: εὐδαιμονία) is a classical Greek word commonly translated as 'happiness'. Etymologically, it consists of the word "eu" ("good" or "well being") and "daimōn" ("spirit" or "minor deity", used by extension to mean one's lot or fortune). Although popular usage of the term happiness refers to a state of mind, related to joy or pleasure, eudaimonia rarely has such connotations, and the less subjective "human flourishing" is often preferred as a translation.[1]

Contents[show] |

[edit] Greek philosophy

| The Utilitarianism series, part of the Politics series |

|---|

| Portal:Politics |

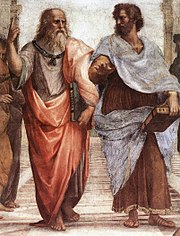

Socrates' philosophy, as it is represented in Plato's early dialogues, contains two related claims about eudaimonia. The first is the strong inter-dependence of eudaimonia, virtue (aretē), and knowledge (epistemē): virtue is a sort of knowledge, perhaps 'knowledge of good and bad', and it is this knowledge that is required to reach the ultimate good, with eudaimonia being the prime candidate for this ultimate good. The second, sometimes called "psychological eudaimonism" or "Socratic intellectualism", is the claim that the ultimate good, eudaimonia, is what all human desires and actions aim to achieve.

Plato's middle dialogues present a somewhat different position. In the Republic, we find a moral psychology more complex than psychological eudaimonism: we do not only desire our ultimate good; rather the soul, or mind, has three motivating parts - a rational, spirited (approximately, emotional), and appetitive part - and each of these parts has its own desired ends. Eudaimonia, then, is not simply acquired through knowledge, it requires the correct psychic ordering of this tripartite soul: the rational part must govern the spirited and appetitive part, thereby correctly leading all desires and actions to eudaimonia and the principal constituent of eudaimonia, virtue.

The pursuit of eudaimonia is the central theme of Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics. Aristotle claims that "every art and every scientific inquiry, and similarly every action and purpose, may be said to aim at some good. Hence 'the good' has been well defined as that at which all things aim." According to Aristotle, the hierarchy of human purposes aim at eudaimonia as the highest, most inclusive end. This is the end to which everyone in fact aims. Further, it is the only end towards which it is worth undertaking a means. Eudaimonia is constituted, according to Aristotle, not by honor, or wealth, or power, but by rational activity in accordance with virtù over a complete life. Such activity manifests the virtues of character, including, honesty, pride, friendliness, and wittiness; the intellectual virtues, such as rationality in judgment; and non-sacrificial (i.e. mutually beneficial) friendships and scientific knowledge (knowledge of things that are fundamental and/or unchanging is the best).

Epicurus agrees with Aristotle that eudaimonia is the highest good. However, unlike Aristotle, he identifies eudaimonia with pleasure. Epicurus presents two main arguments. The first defends the claim that pleasure is the only thing that people value for its own sake. The second, which fits in well with Epicurus' empiricism, supposedly lies in one's introspective experience: one immediately perceives that pleasure is good and that pain is bad, in the same way that one immediately perceives that fire is hot. Thus, as something immediately apparent, no further argument is needed to show the goodness of pleasure or the badness of pain. Although all pleasures are good and all pains evil, Epicurus does not believe that all pleasures are choiceworthy or all pains unchoiceworthy. Instead, one should calculate what is in one's long-term self-interest, and forgo what will bring pleasure in the short-term if doing so will ultimately lead to pain in the long-term.

The Stoics believe that virtù is necessary and sufficient for eudaimonia. Virtù consists of living according to Nature, so eudaimonia is achieved by living according to Nature's will. However, no one (except the fictional "sage") can ever achieve perfect virtù, and everyone is always equally and completely vicious. The best a non-sage can do is to act "befittingly," or in the same way that a perfectly virtuous sage would in the same situation. No one will ever achieve perfect virtù, and therefore eudaimonia, but one can approach it.[2]

[edit] In popular culture

Paul Gilbert has a song on his album Silence Followed by a Deafening Roar titled Eudaimonia Overture.

In Sid Meier's Alpha Centauri, Eudaimonia is refered as a technological advance wich permits an "eudaimonic" future social engineering.

[edit] References

[edit] Further reading

- McMahon, Darrin M., Happiness: A History, Atlantic Monthly Press, November 28, 2005. ISBN 0871138867

- McMahon, Darrin M., The History of Happiness: 400 B.C. - A.D. 1780, Daedalus journal, Spring 2004.

[edit] See also

| |||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder

Not: Yalnızca bu blogun üyesi yorum gönderebilir.